In August 1939, as part of war preparations, the organisation of a transit camp, or a Dulag, started in the north-eastern part of Görlitz-Ost. Görlitz, a fairly large town with a population of about 95,000, located in the Silesian province of the Reich, stretching on both sides of the Neiße River, met the expected conditions. In the eastern, poorer part of the town, a Wehrmacht garrison was stationed. In the military administrative structure, Görlitz was subordinate to the 8th Military District in Breslau (Wrocław), so the Görlitz-Ost stalag was given the number VIII and the letter A as the first of the camps created here.

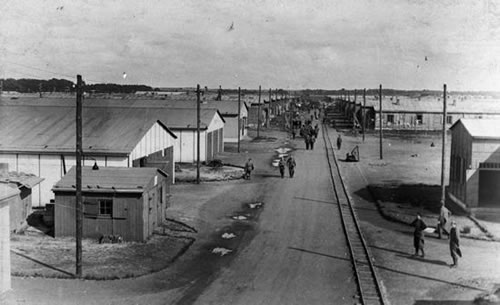

This is where the first prisoners of the Second World War – soldiers of the Polish Army – were brought, and it was with their hands that the proper stalag was then erected at a different location. It was situated in the Moys district (presently Zgorzelec Ujazd), in the south-eastern part of Görlitz-Ost.

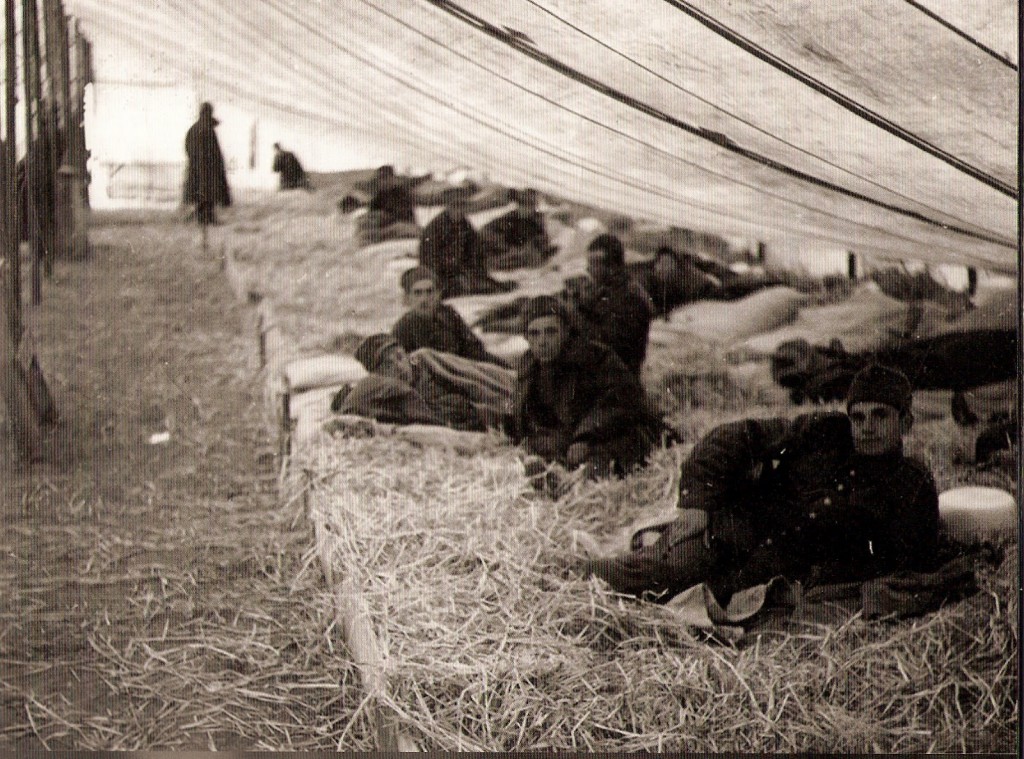

These first prisoners, more than 8,000 people, had to survive through a cold, rainy autumn and an extremely harsh 1939/1940 winter accommodated in large canvas tents. One can only imagine what they experienced: the bitterness of Poland’s military defeat, the slavery, the knowledge about the German occupation of the country, the uncertainty of their future fate, the cold and malnutrition, or actual starvation.

It should be stressed that despite Germany’s commitment to comply with the Geneva Convention, its provisions were applied to prisoners from Eastern European countries to a limited extent, if at all. It was argued that after the occupation of the Polish territory by Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939, the Polish state ceased to exist, so it cannot be a subject to international law. This brought some tragic consequences for Polish prisoners of war. Upon taken captive, they were investigated under charges of crimes against the Germans, and in case of even the slightest suspicion they were immediately shot. Those suspected of “hostile intent towards the Reich” were sent to concentration camps.

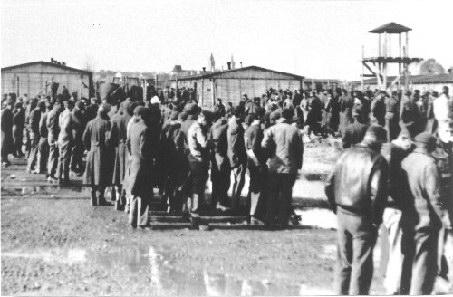

In harsh winter conditions, Polish prisoners of war would built barracks, initially wooden, later brick ones, and the remaining infrastructure of Stalag VIII A, which began to operate in late December 1939. Although most of the Polish prisoners of war were moved to other camps before the spring of 1940 (about 1,400 Polish soldiers remained there), the stalag was still being expanded; the Reich’s war plans included further attacks on the Netherlands, Belgium and France. Since June 1940, transports of Belgian and French prisoners of war began to arrive – about 20,000 of them only that summer.

In June 1941, more than 2300 Yugoslavian POWs, mainly of Serbian nationality, arrived at the camp; Croatian and Macedonian nationality prisoners were released after the end of the Balkan campaign in Yugoslavia. Very strict rules were introduced concerning Serbian prisoners of war, with death penalty for even minor transgressions.

The period between December 1941 to January 1942 saw the first small transport of Soviet prisoners of war coming to Stalag VIII A. Within just over a year, by November 1943, Soviet POWs became the largest group in the camp. There were about 14 thousand of them at that time, to increase to over 16 thousand in January 1945. They consisted of various nationalities from all the republics making up the Soviet Union. Ukrainians were a particularly large group.

In the autumn of 1943 prisoners of the British Armed Forces arrived in the stalag. Following the English were Canadians, New Zealanders and South Africans. After Italy had joined the Allies in late summer 1943, the Germans took captive the Italian army units stationed in the occupied territories of France, Greece and the Aegean Islands. Initially interned, they were transported to POW camps in the following months. They found themselves in Görlitz-Ost in December 1943. As “traitors” they were treated in a particularly brutal manner.

In late 1944, a small group of Polish prisoners of war, AK soldiers, participants of the Warsaw Rising, and 1,748 Slovaks, soldiers of the Slovak national uprising, were sent to the camp. Early January 1945, 1,800 American prisoners of war were brought to the stalag from other camps. It is estimated that throughout the camp’s operation, about 100-120 thousand prisoners of many nationalities passed through its gates.

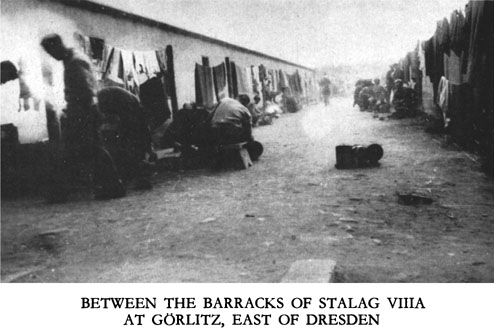

POWs were meant to be and were in fact used as cheap labour force. As the Reich’s war effort escalated and the successive generations were sucked into the German industry needs, a shortage of hands to work soon began to loom over the country. Working troops consisting of a few to several dozen people were created and sent to work in various sectors of the economy – mines, industrial plants, quarries, farms, but also, contrary to the Geneva Convention rules, in the arms industry. Stalag VIII A prisoners were put to work in the vicinity of Görlitz, but also in other Silesian districts, e.g. Soviet POWs worked in the working divisions in the quarries in Strzelin and Szklarska Poręba.

The hard work was accompanied by malnutrition and disease. Pharmaceuticals and medical equipment were in shortage. As some of the prisoners were physicians, the Germans engaged them to medical and sanitary care task, which augmented the situation to some extent only. Whenever an epidemic broke out, they were helpless.

Despite these ominous conditions, some cultural life was taking place in the stalag: an amateur theatre, music bands, orchestras (French and Belgian) and a library were in operation. Sports, self-education and artistic activities were also developed. All these activities were a form of escape from the hopelessness of life in captivity.

Religious practices also played an important role. The camp had a chapel, where services were held in the winter months, and the space served as library on a daily basis. In spring and summer, services were taking place outdoors. The figure that warrants a special mention among Catholic priests and ministers to the prisoners of war was Father Franz Scholz, the parish priest of St. Boniface in Görlitz-Ost.

Soviet nationality POWs were completely excluded from these activities. They suffered a particularly tragic fate. Due to Stalin’s failure to sign the Geneva Convention, they enjoyed no protection and were subject to inhuman treatment. Isolated from the rest of the prisoners, they were forbidden any contact with others. Food rations were kept below the survival minimum, people were cramped in unheated barracks or tried to endure outdoors, stricken with epidemics, with no hope for medical care. The able-bodied were sent to the most exhausting tasks, which killed them en masse. They were also executed on a schedule basis – this concerned mainly political commissioners, but also party functionaries, intelligentsia and Jews. The dead were thrown into nameless pits, lime thrown over and covered with soil. In Stalag VIII A about 10 thousand Soviet prisoners of war lost their lives.

Staring in January 1945, the camp was gradually evacuated, despite difficult winter conditions. Prisoners of war walked in columns westwards to Hesse and western Thuringia (9th Military District) and west Bohemia and northern Bavaria (13th OW). The sick and those unable to march were left behind. They were found on 8 May 1945, in the former camp site, by the first Red Army patrols.